Doctors share why you may not want to wait out the discomfort of this middle-age malady

It can develop after an injury or out of the blue: One day you wake up with intense pain in your shoulder, and over the next few weeks the joint grows so stiff that your range of motion becomes severely compromised.

Known as frozen shoulder (aka, adhesive capsulitis), this mysterious condition usually occurs between the ages of 40 and 65 and affects more women than men. “It’s an interesting process, and it only happens to shoulders; we don’t see frozen knees or frozen elbows,” says Brian Feeley, M.D., a professor of orthopedic surgery at the University of California, San Francisco.

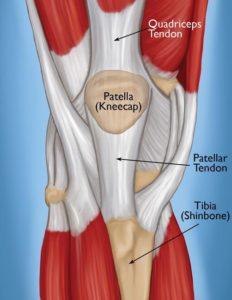

The problem arises where the head of the humerus, or upper arm bone, fits into a shallow socket in the shoulder blade — more specifically, in the shoulder capsule, which is the strong connective tissue surrounding the joint. “The name adhesive capsulitis says a lot because the [shoulder] capsule is the problem — there’s inflammation of the sac the shoulder lives in, and adhesive means it gets stuck after a while,” explains Beth Shubin Stein, M.D., an associate attending orthopedic surgeon and codirector of the Women’s Sports Medicine Center at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City.

The three stages of a frozen shoulder

In the early phase, the shoulder simply hurts and the pain gradually worsens. The second stage is the frozen stage, when the shoulder loses range of motion and “the capsule becomes thicker from inflammation,” notes Shubin Stein. The third stage, called the thawing phase, brings a gradual improvement to the shoulder’s range of motion. How long someone will spend in each stage is unpredictable and varies significantly from one person to the next, but the condition can take six months to two years or longer to resolve.

The exact causes of frozen shoulder remain a mystery, which is why it’s often referred to as idiopathic (meaning, of unknown cause). What is known is that it likely involves an element of inflammation, which triggers the release of chemicals that irritate the joint, causing pain, explains Jon J.P. Warner, M.D., cochief of the MGH Shoulder Service in Boston. “That, in turn, causes the release of other chemicals that cause stiffness or freezing and scarring.” More often than not, frozen shoulder affects the non-dominant arm, and if someone develops idiopathic frozen shoulder in one shoulder, she’s at higher risk for getting it on the other side later, Warner says.

Your risk factors for feeling the freeze

Research has found that people with diabetes are five times more likely to develop adhesive capsulitis; those with thyroid disorders have a nearly three times higher risk of developing the condition. More common in women overall, frozen shoulder can also happen after breast cancer treatment or heart surgery, Warner explains. And there appears to be a genetic predisposition to frozen shoulder, meaning that if a first-degree relative had it, you may have a higher risk.

In 2013, Stacey Marnell, a social worker and school counselor who lives in Takoma Park, Maryland, experienced pain and gradual stiffening in her right shoulder, which progressed to the point where she couldn’t lift her right arm above shoulder level. “My doctor said I was a triple threat for frozen shoulder because I have type 1 diabetes, I take thyroid medications and I’m a petite woman,” says Marnell, 67. “I felt desperate because it was limiting everything I could do — I couldn’t do zippers or buttons on my back, open a window or dry my hair.”

Addressing the problem

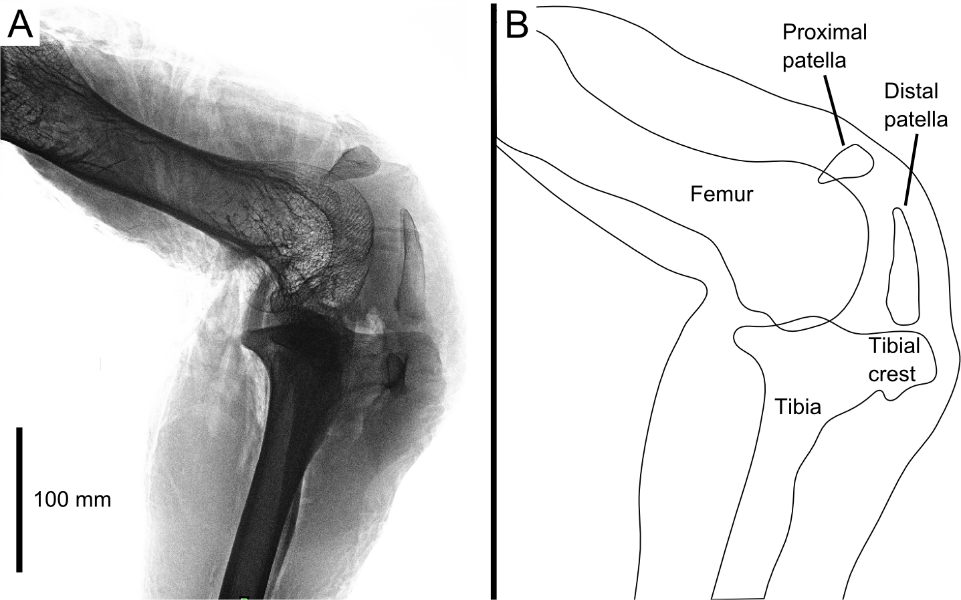

A doctor can diagnose frozen shoulder based on a patient’s description of when symptoms began and when the pain occurs, as well as by doing a physical exam. Identifying loss of active motion (voluntarily being able to move the affected arm and shoulder in certain directions) and loss of passive motion (when the physician tries unsuccessfully to move the arm/shoulder in different directions) is key to making the proper diagnosis, Warner says. An X-ray is taken to rule out the possibility of arthritis in the shoulder causing the limited motion.

“For a long time the treatment was benign neglect, because if you don’t do anything, it will eventually go away,” Shubin Stein says. “But it’s a miserable path for those two years.” And sometimes the recovery process takes longer and can leave the person with permanent losses to their range of motion, she adds.

These days, more cases are addressed, though “treatment is complicated because a lot of things work, but nothing works perfectly,” Feeley says. The goals are to “increase range of motion in the affected shoulder and to decrease the cascade of inflammation and scarring in the capsule.” The general approach to treatment involves anti-inflammatory medications — taken orally or given as a cortisone injection into the shoulder joint if frozen shoulder is in an early stage — and physical therapy. With PT, specific exercises are performed to gently stretch the tissues in the shoulder and improve range of motion — through external rotation and things like crossover arm stretches, for example.

Is There a COVID-19 Connection to Frozen Shoulder?

Following anecdotes about middle-aged COVID-19 survivors subsequently developing frozen shoulder, researchers explored the possible link in a study that was published in the July 2021 issue of the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. They confirmed what they call a possible association between the disease and the shoulder condition. Interestingly, those who had asymptomatic or mild COVID-19 infection had higher rates of frozen shoulder.

The researchers theorize that the link between the two may be due to COVID-19’s direct infection of the cells outside the respiratory tract, as well as from “a cytokine storm and a systemic inflammation that may impact nearly every organ system, including the musculoskeletal tissues.”

Though he hasn’t seen this pattern in his practice, orthopedic surgeon Feeley says, “It makes sense that some people who develop COVID, which causes an intense immune reaction, are going to end up with frozen shoulder. There could be a relationship [with the virus], but it hasn’t been clearly defined.” Experts have also suggested that factors such as being sedentary while sick during COVID-19 could play a role.

Maria Leonard Olsen’s frozen shoulder started as mild pain in her right shoulder. From there it gradually became more and more difficult to lift her arm as the discomfort worsened. “It’s a weird, throbbing pain; it’s so intense, and then it just stops,” says Olsen, 58, a lawyer and writer in Bethesda, Maryland. This past July, she saw an orthopedic surgeon, who made the diagnosis, gave her a cortisone shot and sent her for PT twice a week. “It’s about 50 percent better now,” she says, both in terms of movement and pain.

If the more conservative treatments don’t help, surgery may be an option during stage 2 of frozen shoulder. With a procedure called arthroscopic capsular release, an orthopedic surgeon releases the stiffened joint capsule and removes adhesions (scar tissue), Warner explains. Surgery is usually followed by intense PT to help the patient maintain the restored range of motion.

To treat her (right) frozen shoulder, Marnell went for physical therapy and dry needling (which involves inserting super thin needles into muscles, tendons, ligaments or other tissues to increase range of motion and reduce pain). The combination helped a bit but not completely. Meanwhile, her left shoulder started stiffening up, and it didn’t respond to stretching, PT, massage or acupuncture. (While there’s little scientific evidence that acupuncture or dry needling helps, these techniques may be helpful as adjunctive therapies, Shubin Stein says.) In 2015, Marnell had arthroscopic surgery on her left shoulder to break up the frozen tissue, followed by intense PT. These days she has nearly full mobility in both shoulders.

To maximize recovery from frozen shoulder, early diagnosis is important, experts say. If shoulder pain is waking you up at night, if you’re losing range of motion (especially when rotating your shoulder inward), or if fast motions with your upper arm hurt more than slow motions, see a doctor. “Early intervention and diligent treatment make this a much quicker process if we catch it before scarring occurs,” Shubin Stein says.